by Carol Colborn

At the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898, Spain ceded the Philippines to the US. The US built three major military bases: Subic Naval Base in Zambales, Clark Air Force Base in Pampanga, and Fort Mills in Corregidor. The islands became a major battlefront in the Pacific during WWII. For a Filipino-American couple like us, this piece of history takes on significance of more than double proportions.

In Bill’s first visit to the Philippines in 2009, I took him to Subic and Clark. Subic Base, a major ship-repair, supply, and rest and recreation facility of the US Navy, was the largest overseas military installation of the United States Armed Forces after Clark Air Base. Since the bases turnover to the Philippine government in 1991, it has become an industrial park, a tourist resort, and a residential haven.

One of my friends, Charo Simons now lives in a great former officer’s home for a mere $50,000 long-term lease. She works for the Chairman of the Subic Bay Development Corporation which manages the area. The tourist duty free shops still offer many a bargain, the beaches still look very inviting, and the hills still offer good jungle trips. Regularly, planeloads of Asians are brought to its casino for a gambling weekend. FedEx and other industrial companies have built hubs there.

When we went to HongKong, we departed from the Clark International Airport. Unlike Subic, it looks like Clark is dying. It should be an ideal place for a major airport (bus trip from Manila, 1 ½ hours) because of all the facilities and land (14.3 sq mi with a military reservation extending north at another 230 sq mi). The base was a stronghold of the combined Filipino and American forces and was a backbone of logistical support during the Vietnam War. Bill was able to fly a plane at a Clark flying school in 2009.

We had a few hours before boarding our plane, so we hired a van to take us around. We discovered a lonely Goddess of Peace memorial from Japan, the controversial white elephant project of former President Fidel Ramos, and empty hotels and duty-free shops. But the Villages, home of the native Aetas in the surrounding hills, was our pleasant discovery. We even witnessed a cow being butchered in the fields and a wedding party being held.

Coming back from HongKong, we stayed in Clark for the night and BFFs Ann and Jingjing picked us up in Dittas’s car (she is in Colombo, Sri Lanka, heading an IT company). We first had the famous pizzaninis at C! and then took the SCTEX, the new interchange connecting Subic and Clark, and proceeded to Montemar Beach in Mariveles, Bataan, where Jingjing is a member.

On Dec. 7, 1941 the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Four months after, Bataan fell to the Japanese. 75,000 Fil-Am soldiers were forcibly transferred to the POW camp in Capas, Tarlac. The 60 mi Death March resulted in very high fatalities inflicted upon prisoners and civilians alike, and was later judged by an Allied Military Commission to be a Japanese war crime.

It started in Mariveles near Montemar and markers are regularly placed on the road retracing the infamous route. On the way there, we paid tribute to Filipino heroes at Mt. Samat, the huge cross on top of the mountain, a memorial to those who suffered in the March. In Acuzar, a town before Mariveles, is Las Casas Filipinas (Philippine Houses) by the sea, a neat cluster of restored ancestral Filipino homes brought there piece by piece. Montemar is a very nice exclusive beach resort (we rejoiced with Filipinos all over the world as we watched the Pacquiao-Mosley fight there).

The strategic location of Corregidor Island at the mouth of Manila Bay prompted the Americans to make it an ‘impregnable fortress’. During World War II, Corregidor played an important role during the invasion and liberation of the Philippines from Japanese forces. The hydrofoil trip to the island was just 1 ½ hours from the Folk Arts Theatre area in the reclaimed land on Manila Bay. Colorful tramvias, replicas of the trollies they used then took us around the island.

The skeletons of heavily bombed Mile-long Barracks (the longest single military barracks in the world housing 8,000 soldiers) and the remains of the cross-shaped Hospital which the Japanese destroyed despite war treaties were spectacles of the gruesome battle that lasted five months. And the fitting tributes to the brave soldiers are many: the Pacific War Memorial (with its altar and Eternal Flame), the Filipino Heroes Memorial with 14 murals of Philippine history, and the statue of Gen. Macarthur who escaped to Australia from where he declared, ‘I shall return’. Corregidor was retaken 3 years after.

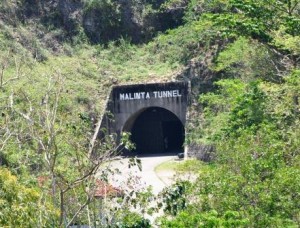

The Malinta Tunnel Night Tour is the most descriptive of the life of soldiers on the fortress. It is a 2.5 mile network of laterals on Malinta (full of leeches) Hill. At times bending low to pass through narrower sub-laterals, we experienced utter darkness, felt whiffs of cooler air from air passages, visited the 1,000 bed hospital that replaced the destroyed hospital outside, retraced the escape route of Gen. MacArthur, inspected the quarters of President Quezon, the petroleum storage facilities, the quarters, and even the femur bone of a Japanese soldier who may have committed hara-kiri on the retaking of the base.

Reliving WWII in the Philippines gave me memories of my father who fought with American soldiers and my mother, a teacher who learned Japanese in order to be able to interpret for Filipinos. They met during the war (my father was assigned to her province, Batangas) and I was born 2 years after it ended. Taking this trip with Bill, my American husband, made it even more significant! It reminded us once again of the closeness of Filipino-American relations.